Behind the glamour, Europe’s architectural profession is going through rapid changeBehind the glamour, Europe’s architectural profession is going through rapid change

Released on Thursday, October 16th in The Economist

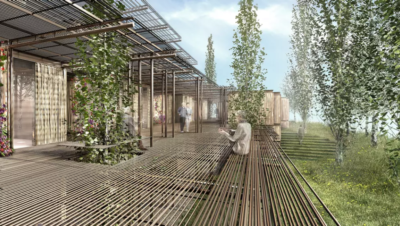

At a glitzy £180 ($288) a head reception held on October 16th, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) declared that the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool (pictured) by Haworth Tompkins had won this year’s Stirling prize, Britain’s most prestigious award for architects’ buildings. It had fought off a tough set of competing designs, which included Zaha Hadid’s London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympic games and the Shard, Britain’s tallest skyscraper. The glamour of the six buildings shortlisted for the award may at first make the architecture business seem that it is going from strength to strength. But behind the glitz is an industry suffering from shrinking demand and rapid structural change.

The market for architectural services in Britain and across Europe has been hit hard since the financial crisis. Between 2008 and 2012 the sector shrank by 28% according to the Architects Council of Europe (ACE), an industry body—much faster than falls in GDP or construction output. In Britain, architects suffered much worse, as the demand for their services shrank by as much as 40%, the RIBA reckons.

Since 2012, even as Europe’s construction sector began to grow again, the demand for architectural services has flatlined. Structural factors unrelated to construction volumes seem to explain the profession’s relative decline. Other professionals offering similar services, such as engineers and surveyors, have continued to poach some of their workload since the recession. Worse still, their main business—designing new buildings—has come under threat from a shift towards cheaper system-building methods, minimising the need for their pricey bespoke design services. Many commercial buildings, such as the latest generation of hotels built by Travelodge, a budget chain, are now made of prefabricated containers in order to cut down on designers’ fees. Governments are also promoting modular construction, which requires less input from architects, partly because of the technique’s eco-friendly credentials. The European Commission has said that by 2020 it wants 5% of new buildings to be built out of prefabricated panels made of straw.

In spite of falling workloads, the number of architectural practices across Europe has increased since 2008. But this has substantially been the result of architects at small- and medium-sized firms being forced to go freelance: 80% of practices now comprise of less than five people, reckons Ian Pritchard of ACE. To survive, larger practices, such as those that normally win the Stirling prize, have had to look abroad for design work in countries with building booms, such as China and Dubai.

Architects have also been forced to adopt more ingenious ways to cut costs. The use of remote-controlled drones to conduct surveys and take aerial photos has slashed the costs of inspecting tall buildings. The time taken to draw up plans has been reduced by computerised-design systems, such as CAD and BIM. Others have outsourced drawing work to countries including India and Peru to save money.

But even with deep cost-cutting, architects are still struggling to attract clients. In Poland, in spite of construction output growing over the past year, demand for design services has continued to shrink. And in Britain, RIBA data suggest that Britain’s booming construction sector has yet to benefit architects as much as it has builders. Long-term prospects also look dismal. Even in 2025 the construction market in Western Europe will be 5% below its 2007 peak, according to Global Construction Perspectives, a consultancy.

Taken together, this has damaged animal spirits in the industry. At a recent conference in London, one architect said that the traditional small-practice model will face “extinction” within the next decade—a common feeling in some parts of the profession. Put off by the poor job prospects, only about a third of architecture students in Europe now qualify to practise; in the past, the vast majority did. Although builders—and even those using factory-built systems—will always need help with design, fewer architects than ever sit comfortably at the glamorous pinnacle of the construction industry. As Herman Hertzberger, a prize-winning Dutch architect, wryly noted of the profession’s future in 2011, “we’re not buried next to the king any more”.

Main image taken from the article’s website.

Released on Thursday, October 16th in The Economist

At a glitzy £180 ($288) a head reception held on October 16th, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) declared that the Everyman Theatre in Liverpool (pictured) by Haworth Tompkins had won this year’s Stirling prize, Britain’s most prestigious award for architects’ buildings. It had fought off a tough set of competing designs, which included Zaha Hadid’s London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympic games and the Shard, Britain’s tallest skyscraper. The glamour of the six buildings shortlisted for the award may at first make the architecture business seem that it is going from strength to strength. But behind the glitz is an industry suffering from shrinking demand and rapid structural change.

The market for architectural services in Britain and across Europe has been hit hard since the financial crisis. Between 2008 and 2012 the sector shrank by 28% according to the Architects Council of Europe (ACE), an industry body—much faster than falls in GDP or construction output. In Britain, architects suffered much worse, as the demand for their services shrank by as much as 40%, the RIBA reckons.

Since 2012, even as Europe’s construction sector began to grow again, the demand for architectural services has flatlined. Structural factors unrelated to construction volumes seem to explain the profession’s relative decline. Other professionals offering similar services, such as engineers and surveyors, have continued to poach some of their workload since the recession. Worse still, their main business—designing new buildings—has come under threat from a shift towards cheaper system-building methods, minimising the need for their pricey bespoke design services. Many commercial buildings, such as the latest generation of hotels built by Travelodge, a budget chain, are now made of prefabricated containers in order to cut down on designers’ fees. Governments are also promoting modular construction, which requires less input from architects, partly because of the technique’s eco-friendly credentials. The European Commission has said that by 2020 it wants 5% of new buildings to be built out of prefabricated panels made of straw.

In spite of falling workloads, the number of architectural practices across Europe has increased since 2008. But this has substantially been the result of architects at small- and medium-sized firms being forced to go freelance: 80% of practices now comprise of less than five people, reckons Ian Pritchard of ACE. To survive, larger practices, such as those that normally win the Stirling prize, have had to look abroad for design work in countries with building booms, such as China and Dubai.

Architects have also been forced to adopt more ingenious ways to cut costs. The use of remote-controlled drones to conduct surveys and take aerial photos has slashed the costs of inspecting tall buildings. The time taken to draw up plans has been reduced by computerised-design systems, such as CAD and BIM. Others have outsourced drawing work to countries including India and Peru to save money.

But even with deep cost-cutting, architects are still struggling to attract clients. In Poland, in spite of construction output growing over the past year, demand for design services has continued to shrink. And in Britain, RIBA data suggest that Britain’s booming construction sector has yet to benefit architects as much as it has builders. Long-term prospects also look dismal. Even in 2025 the construction market in Western Europe will be 5% below its 2007 peak, according to Global Construction Perspectives, a consultancy.

Taken together, this has damaged animal spirits in the industry. At a recent conference in London, one architect said that the traditional small-practice model will face “extinction” within the next decade—a common feeling in some parts of the profession. Put off by the poor job prospects, only about a third of architecture students in Europe now qualify to practise; in the past, the vast majority did. Although builders—and even those using factory-built systems—will always need help with design, fewer architects than ever sit comfortably at the glamorous pinnacle of the construction industry. As Herman Hertzberger, a prize-winning Dutch architect, wryly noted of the profession’s future in 2011, “we’re not buried next to the king any more”.

Main image taken from the article’s website.