Architect whose masterplan for the 1992 Olympics created a lasting legacy for the city of Barcelona

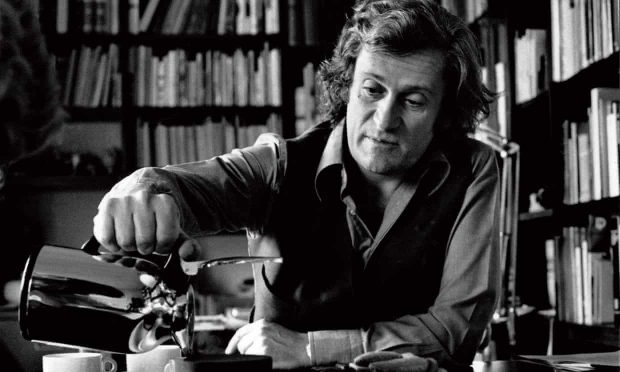

The Guardian, December 2r4, 2021 | Photo: Oriol Bohigas in 1974. His ‘Barcelona model’ for the 1992 Olympics informed London’s approach in 2012. Photograph: Album/Alamy

Known as the masterplanner of the successful 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, the architect Oriol Bohigas, who has died aged 95, was a fierce defender of urban planning as a political and social act. He played a critical role in the cultural and political life of his city, influencing generations of urban theorists and practitioners.

As leader of Barcelona’s urban planning department in the mid-1980s, Bohigas conceptualised and implemented the “Barcelona model” that formed the urban backbone to the city’s Olympics. This event and its lasting legacy put the grey, debilitated but fiercely independent city, punished by decades of Francoism, firmly on the international map. Twenty years later, the Barcelona model informed London’s approach of using the Olympic Games as an opportunity to create an integrated piece of city with housing and amenities for the capital’s more deprived neighbourhoods.

With the death of Franco in 1975, Barcelona had grasped the opportunity to democratise and modernise. Working closely with the first socialist mayors of the post-Franco era, Narcís Serra and Pasqual Maragall, Bohigas created the intellectual and spatial armature for its transformation. He was committed to innovation through continuity rather than aggressive rupture and restructuring, and recognised that the public spaces of the city – the pavements, streets, squares, parks, beaches and waterways – should be at the heart of a democratic vision of the contemporary city.

Bohigas built on the canonical work of the father of modern urbanism, Ildefons Cerdà, who in the mid-19th century had created a plan for the growing city with an elegant and functional diagonal grid known as the Eixample. With its tree-lined avenues and pedestrian friendly ramblas, generous public spaces and community parks, Cerdà’s Grid served the city well. Bohigas re-interpreted this model for the 20th century, upgrading the public realm, intensifying its local neighbourhoods and reuniting the city with its seafront on the Mediterranean.

“Monumentalise the periphery; functionalise the centre” was Bohigas’ linguistically obtuse slogan for re-energising Barcelona. This translated into a focused programme of interventions that gave dignity to deprived neighbourhoods – such as the working-class district of Poble Nou – and made the dense inner-city districts more liveable, with pocket parks, markets, play areas and local amenities.

In the space of two decades much was achieved. In recognition of this collective effort, the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) broke with tradition in 1999 and awarded the City of Barcelona – and not an individual or group of architects – the royal gold medal. Bohigas was one of five individuals singled out in the citation.

Equally sharp in manner of speech and dress – he spoke in short, staccato sentences delivered with rasping gravitas and wore immacutely ironed shirts, linen jackets and colourful socks – Bohigas had the air of a fin-de-siècle aesthete but the mind of a pragmatist. He was outspoken, often pugnacious, but always with a glint in his eye. He was keen to get things done, and resigned as elected councillor in charge of culture in 1991 when he felt Maragall was too slow in implementing one of his pet projects for neighbourhood libraries.

Born in Barcelona, Oriol was the son of middle-class Catalan intellectuals, Maria Guardiola and Pere Bohigas, a professor of linguistics. His high school friend Josep Martorell convinced him to enrol in 1943 at Barcelona’s school of architecture, ETSAB, which he would go on to lead as director from 1977 to 1980.Advertisementhttps://91b047882ff52995db26b6f6f4b23622.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

In his 30s, he formed the militantly pro-modern R Group and had the temerity to write to the architect Mies van der Rohe to propose the reconstruction of his elegantly minimalist Barcelona Pavilion, which had been designed for the 1929 International Exposition and torn down the following year. Happily, this plan was realised in 1986 and the reconstructed modern masterpiece stands in Montjuïc Park.

With Martorell and David Mackay, Bohigas formed MBM Arquitectes, one of Spain’s most successful design practices, with a significant portfolio of public and private buildings that adhered to the principles of low-key, contextual modernism. Their buildings prioritised the relationship to the city rather than gymnastic self-promotion. For example, their design for the 1992 Olympic Village is memorable for the way in which the layout of the urban blocks opens out towards the sea, reconnecting the old city with its waterfont.

Bohigas provided the critical intellectual and theoretical underpinning to the practice. He was a founding member of the publisher Edicions 62, an editor of the journal Arquitecturas Bis (1974-85) and chair of the Fundació Joan Miró museum (1981-88). He published more than 15 books, including Barcelona Entre el Pla Cerdà i el Barraquisme (1963, Barcelona Between the Cerdà Plan and Shanty-towns ). He argued strongly for the social responsibility of the architect. In a letter addressed to a member of the urban planning commission of Barcelona city council in 1964, he made his view explicit: “To be an urban planner is to begin to be a socialist now.”Advertisementhttps://91b047882ff52995db26b6f6f4b23622.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-38/html/container.html

Together with the director of urban projects of Barcelona city council, Josep Acebillo, Bohigas was responsible for selecting some of the most talented final-year students – the so-called “golden pencils” – from the ETSAB architecture school and giving them responsibility for coming up with ideas for individual city districts. He also played an important role in attracting international figures, from Arata Isozaki to Frank Gehry, to build in Barcelona and giving opportunities to locally trained, younger architects to make their mark on its urban landscape.

Bohigas believed that the cumulative effect of small, “punctual” projects – often referred to as urban “acupuncture” – could be more effective than large-scale, complex initiatives that took years to implement and required budgets that did not exist in Spain’s fragile early democracy. This approach can be seen as a precursor to the current vogue for “tactical urbanism”, whereby small-scale improvements – pavement widening, outdoor seating, street closures, tree-planting – are implemented quickly and on a temporary basis in close cooperation with local communities.

In the 1960s and 70s, Bohigas was associated with Gauche Divine, a group of left-leaning intellectual bourgeois artists, film-makers, philosophers and artists who met regularly at the Boccaccio discotheque in Barcelona. Their spirit shaped not only his professional but also his social life. In the late 1970s, Bohigas and his partner, the landscape architect Beth Galí, turned their apartment in Plaça Reial – in what was then a run-down area of the old city – into a salon of international cultural exchange and heated debates on city politics.

Bohigas, often accompanied by whiskey and a cigar, would argue deep into the night with professionals and politicians of different generations and persuasions in one of the most beautiful squares at the very heart of his beloved city.

He is survived by Beth; by his wife, Isabel Arnau, from whom he was separated, and their five children, Josep, Gloria, María, Eulalia and Pere, nine grandchildren and a great-granddaughter.

Oriol Bohigas i Guardiola, architect, born 20 December 1925; died 30 November 2021